Tall, bearded and wearing a pained expression, an elderly Saudi man called Jaber stands before the ruins of his family house in the town of Najran, just north of the border with war-torn Yemen.

The whitewashed walls of his house are pockmarked with blast marks and jagged holes gouged by flying shrapnel.

“Yesterday at 5.15 in the afternoon,” he told me, “came an explosion from Yemen. My family were sitting just over there,” he pointed to an abandoned mattress on the ground.

“Thank God they survived. In this house there are five families living here… There are children and women and old men here. What have they done to deserve this? It is not right.”

Image copyrightFRANK GARDNER

Image copyrightFRANK GARDNERShortly after we left, seven more missiles landed in the neighbourhood, injuring several people and reportedly killing two.

Saudi Civil Defence workers say they were fired indiscriminately by Houthi rebels from across the border in Yemen.

Read more:

- How bad is the humanitarian crisis?

- Terror of life under siege

- Dying in silence in Yemen

- The man who lost 27 relatives in an air strike

- Practising medicine under fire

Maimed by shrapnel

Saudi Arabia is at war.

You wouldn’t know it on the peaceful streets of its capital, Riyadh, but hundreds of miles to the south the civil war that has torn apart neighbouring Yemen is spilling over the border into Saudi towns and villages.

Saudi officials say more than 500 of their citizens have been killed by the Yemen war, a number dwarfed by the thousands killed in Yemen itself, but still a shock for this otherwise tranquil kingdom that is home to the holiest sites in Islam and is also the world’s biggest oil producer.

We visited the ruins of a girls’ elementary school in the village of Khawber, hit by a Houthi missile in the middle of the night.

In the shattered classroom the school clock lay on the floor, its hands stopped at the moment the missile exploded.

Image copyrightFRANK GARDNER

Image copyrightFRANK GARDNER Image copyrightDUNCAN STONE

Image copyrightDUNCAN STONEWe met badly injured villagers, maimed by flying shrapnel when a Houthi rocket struck their mosque, and we were given rare access to a Saudi army Patriot anti-missile battery, placed in the desert facing Yemen, that has been intercepting ballistic missiles fired at Saudi Arabia’s southern towns.

These Soviet-era missiles are aimed at the towns of Najran, Abha, Gizan, Khamis Mushayt and even, according to the Saudis, at the holy city of Mecca.

Cyrillic writing

These ageing but still deadly Russian-made missiles belong to a stockpile amassed by the Yemeni army over the years and now taken over by the Houthis.

Image copyrightDUNCAN STONE

Image copyrightDUNCAN STONEThe weapons include Scud B missiles with a payload of nearly one tonne of high explosives, and the smaller Tochka with a payload of 482kg of explosives.

Saudi officers showed us the remnants of a downed Tochka, still bearing Cyrillic writing on its fuselage.

Between 6 June 2015 and 26 November 2016 the Saudi authorities have recorded 37 ballistic missiles fired from Yemen across the border into Saudi airspace.

Yet the damage to Saudi Arabia pales before the destruction next door in Yemen.

The war there started in September 2014 when fighters from a minority group, the Houthis, formed an alliance with the ousted former President, Ali Abdullah Saleh, who lent them the support of troops still loyal to him.

The Houthis, who demanded an end to corruption in government and a fairer distribution of power, marched down from their northern mountain stronghold around the town of Saada, took over the capital, Sanaa, dissolved parliament and put the president under house arrest.

Yemen, at the time, was just emerging from the chaos of the Arab Spring, a national dialogue had been completed, a new president chosen and there were high hopes for a peaceful, democratic future.

Both sides blamed

Those hopes were dashed.

The country’s President, Mansour Hadi, fled for his life to the southern port of Aden where the Houthis bombed him from the air in his palace.

Yemen’s legitimate, UN-recognised government, now in exile, appealed for help, and Saudi Arabia, alarmed – at what it saw as a takeover of Yemen by an Iranian proxy – stepped in.

Spearheaded by their newly appointed and then still untested Defence Minister, Prince Mohammed Bin Salman, the Saudis put together a coalition of mainly Arab countries and began a massive air campaign in March 2015.

They aimed to drive the Houthis back from territory they had seized and restore the legitimate government, backed by UN Security Council Resolution 2216.

This has not worked. Today the Houthis remain in control of much of Yemen and the death toll keeps mounting.

Both sides are accused of recklessly targeting civilians – but the UN has said the majority of casualties have been caused by coalition air strikes, a view disputed by both the Saudis and the Yemeni government.

Coalition’s ‘war room’

In a guest palace in Riyadh, where exiled members of the Yemeni government gather, I met Rajhi Badi, their spokesman. He was unequivocal as to where the blame lies.

“There’s only one reason for the destruction in Yemen. It’s the Houthis and the forces of ex-President Saleh.

“They seized the government’s weapons and are using them against Yemeni civilians in built-up areas,” Mr Badi said.

Image copyrightFRANK GARDNER

Image copyrightFRANK GARDNERBut to hear first-hand how the Saudis account for so many civilian deaths, I went to the coalition headquarters in Riyadh to question the Saudi-led command on how they choose their targets, and – more importantly – what measures they take to avoid those civilian casualties.

King Salman Air base is a huge, sprawling, well-guarded base on the edge of Riyadh.

On one of its roundabouts a British-built Tornado jet is mounted, testimony to the multibillion pound ongoing defence sales relationship between Britain and the Royal Saudi Air Force.

Image copyrightFRANK GARDNER

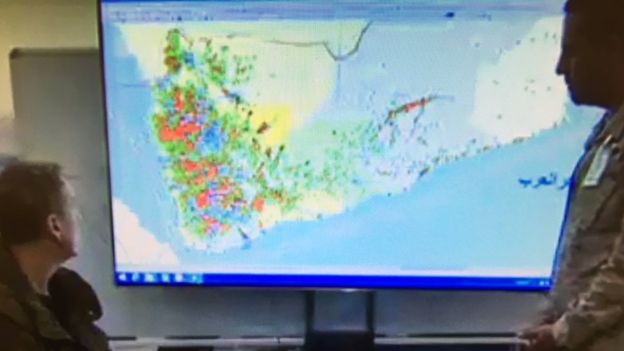

Image copyrightFRANK GARDNERInside the command and control centre there are flags from 11 nations, and uniformed staff and intelligence officers working, from several Arab countries – notably Egypt, the UAE and Jordan, as well as Saudi Arabia.

A dynamic, digital map on the wall display shows the movement of every aircraft on or approaching Yemen.

The coalition has complete air superiority in this war – the Houthis and their backers no longer have an air force.

In a large chamber called the “War Room” a digital chart details the line-up of inbound combat aircraft heading for Yemen.

This is the daily “Air Tasking Order Schedule”. It shows which aircraft are in the air, from which country, their callsigns, and their intended targets (e.g. Egypt – F16 – Callsign Viper – Time on target 1600 – Killbox grid etc.).

Wrong number?

Senior Saudi officers inside the command and control centre insist that when choosing targets in Yemen the coalition abides by the Law of Armed Conflict (LOAC) and that every precaution is taken to avoid civilian casualties.

Image copyrightAP

Image copyrightAP Image copyrightAP

Image copyrightAPYet reports from the ground describe schools, hospitals, factories and social gatherings all being hit from the air.

The worst single event was on 8 October 2016 when a double air strike by a coalition warplane hit a packed funeral hall in the capital Sanaa, killing 140 people, mostly civilians.

The Saudi-led coalition has since admitted it was carried out in error and has offered compensation.

I put it to Maj Gen Ahmed Al-Assiri, the coalition spokesman, that both international aid organisations and the UN blame air strikes for 60% of civilian casualties.

He responded by accusing the UN of being effectively spoon-fed false statistics by the Houthi rebels.

“I think it is a wrong number or it is an exaggerated number when they say 60% of the casualties in Yemen are due to the air strikes.

“They are not on the ground, they are just in Sanaa and they write a report which the Houthis are giving to them.”

No-Strike list

The Saudi officers went to great lengths to insist they comply with international Rules of Engagement (ROE) and the LOAC.

They showed me their “No-Strike List” (NSL) which includes more than 30,000 sites all over Yemen, including refugee camps and hospitals.

Those Rules of Engagement state clearly:

- Do not target any facility identified on the No-Strike List

- Presume all structures, objects, persons in Yemen are civilian unless otherwise apparent

Image copyrightDUNCAN STONE

Image copyrightDUNCAN STONEThey also explained their “Targeting Cycle”, a circular chart detailing how air strikes are planned and executed, including a sign-off by a lawyer for every target chosen by the intelligence cell.

“If we plan a target,” a senior Saudi intelligence officer told me, “it’s going to go through this cycle. If it’s close to a mosque or a hospital then we don’t hit it.”

But I pointed out this is exactly what has been happening, repeatedly, in Yemen, for the past 20 months.

Coalition officers admit there have been some mistakes – but they reminded me that even the US Air Force, with its vast experience, has hit wrong targets in Afghanistan and recently at Deir Az-zour in Syria.

“When you conduct a war in such circumstances,” said Maj Gen al-Assiri referring to Yemen, “where the militias melt in with the civilians, it is too difficult.

“Mistakes could happen, and we do what is necessary to protect the civilians. We are here to protect the civilians, we are not here to harm the civilians,” he added.

Britain’s position

So what is Britain’s role exactly in this messy, seemingly unwinnable war in Yemen?

Britain supplies Tornado and Typhoon aircraft and precision-guided munitions to the Saudi government under defence deals concluded before this war began.

Since the air strikes started in March 2015, the UK has sold over £3.3bn ($4.1bn) worth of defence equipment to Saudi Arabia with more planned.

This has prompted some campaigners to suggest that Britain is complicit in the carnage afflicting Yemen.

Image copyrightEPA

Image copyrightEPAThe British government’s position is that Saudi Arabia is an ally and that it supports its UN-backed actions to restore the legitimate Yemeni government to power.

“This is a legitimate request by the Saudis and the coalition to respond to President Hadi and (UNSC) Resolution 2216 in support of the aggression by the Houthis,” says the Foreign Office Minister responsible for the Middle East, Tobias Ellwood, MP.

“But mistakes have been made, there’s no doubt about that. Attacks have taken place which shouldn’t have taken place, hitting targets on the ground, collateral damage taking place. They need to learn from this.”

Whitehall says RAF personnel placed inside coalition HQ are not involved in the targeting, that they are there to report back as well as to pass on to the Saudi-led coalition their expertise about best practice in avoiding civilian casualties.

The Saudis told me that their air force “takes its Paveway 4 Collateral Damage Chart from the UK’.

This is an interactive diagram composed of a series of questions that help planners decide whether or not a target is at risk of collateral damage (i.e. hitting civilians).

Red line

But regardless of whatever rules are followed in military planning cells in Riyadh, the fact remains that in Yemen, civilians are getting killed and injured by both sides.

The UK government was concerned enough about the funeral bombing in October that the Prime Minister sent the FCO Minister down to Riyadh to press the Saudi and exiled Yemeni governments for a full explanation, which duly followed.

From my several recent visits to Saudi Arabia I get the strong impression that the Saudis never expected the Houthis to hold out as long as they have.

By now, they expected them to have effectively sued for peace, accepted a purely political role in a future Yemeni government and handed over their heavy weapons to the UN.

That still hasn’t happened, and for the Saudis this is a red line.

Time and again they have said they will not allow an armed militia, backed by their rival Iran, to hold onto power illegally in Yemen.

Until one side or the other backs down, this war shows no sign of ending.