On the morning of 16 December 2015 Qatar’s ruling family got bad news: 28 members of a royal hunting party had been kidnapped in Iraq.

A list of the hostages was given to Sheikh Mohammed bin Abdulrahman al-Thani, who was about to become Qatar’s foreign minister. He realised that it included two of his own relatives.

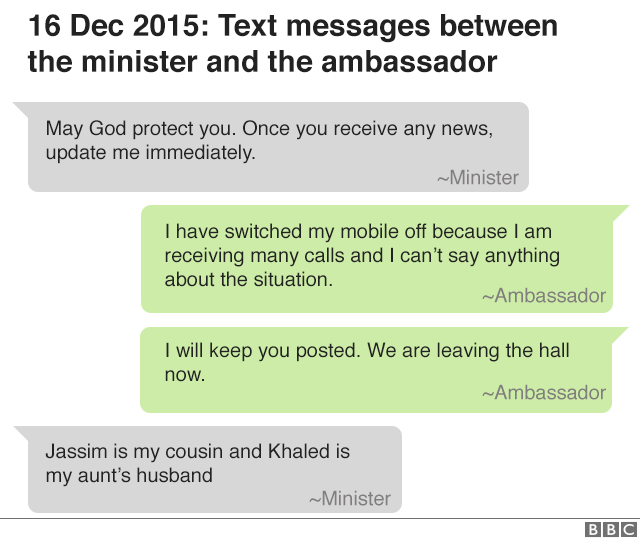

“Jassim is my cousin and Khaled is my aunt’s husband,” he texted Qatar’s ambassador to Iraq, Zayed al-Khayareen. “May God protect you: once you receive any news, update me immediately.”

The two men would spend the next 16 months consumed by the hostage crisis.

In one version of events, they would pay more than a billion dollars to free the men. The money would go to groups and individuals labelled “terrorists” by the US: Kataib Hezbollah in Iraq, which killed American troops with roadside bombs; General Qasem Soleimani, leader of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards’ Quds Force and personally subject to US and EU sanctions; and Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, once known as al-Nusra Front, when it was an al-Qaeda affiliate in Syria.

In another version of events – Qatar’s own – no money was paid to “terrorists”, only to the Iraqi state.

In this version, the money still sits in the Central Bank of Iraq’s vault in Baghdad, though all the hostages are home. The tortuous story of the negotiations emerges, line by line, in texts and voicemails sent between the foreign minister and the ambassador.

These were obtained by a government hostile to Qatar and passed to the BBC.

So, did Qatar pay the biggest ransom in history?

Sheikh Mohammed is a former economist and a distant relative of the emir. He was not well known before he was promoted to foreign minister at the relatively young age of 35.

Image copyrightEPA

Image copyrightEPAAt the time of the kidnapping, the ambassador Zayed al-Khayareen was in his 50s, and was said to have held the rank of colonel in Qatari intelligence. He was Qatar’s first envoy to Iraq in 27 years, but this was not an important post.

The crisis was his chance to improve his position.

The hostages had gone to Iraq to hunt with falcons. They were warned – implored – not to go. But falconry is the sport of kings in the Gulf and there were flocks of the falcons’ prey, the Houbara bustard, in the empty expanse of southern Iraq.

The hunters’ camp was overrun by pick-up trucks mounted with heavy machine guns in the early hours of the morning.

A former hostage told the New York Times they thought it was “Isis”, the Sunni jihadist group Islamic State. But then one of the kidnappers used a Shia insult to Sunnis.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESFor many agonising weeks, the Qatari government heard nothing. But in March 2016, things started to move. Officials learned that the kidnappers were from Kataib Hezbollah (the Party of God Brigades), an Iraqi Shia militia supported by Iran.

The group wanted money. Ambassador Khayareen texted Sheikh Mohammed: “I told them, ‘Give us back 14 of our people… and we will give you half of the amount.'” The “amount” is not clear in the phone records at this stage.

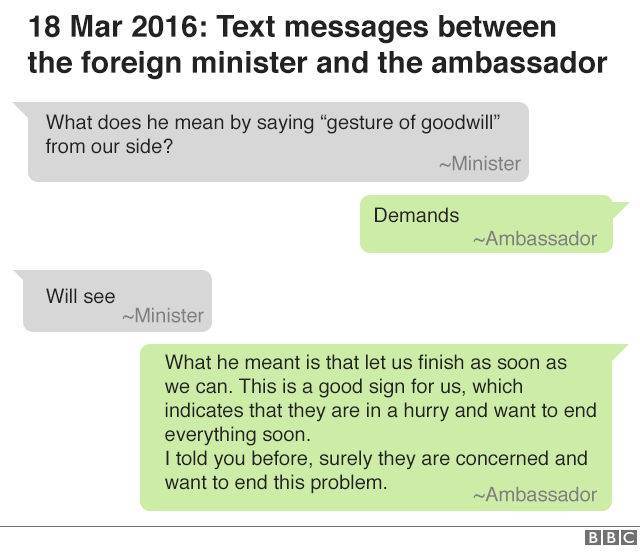

Five days later, the group offered to release three hostages. “They want a gesture of goodwill from us as well,” the ambassador wrote. “This is a good sign… that they are in a hurry and want to end everything soon.”

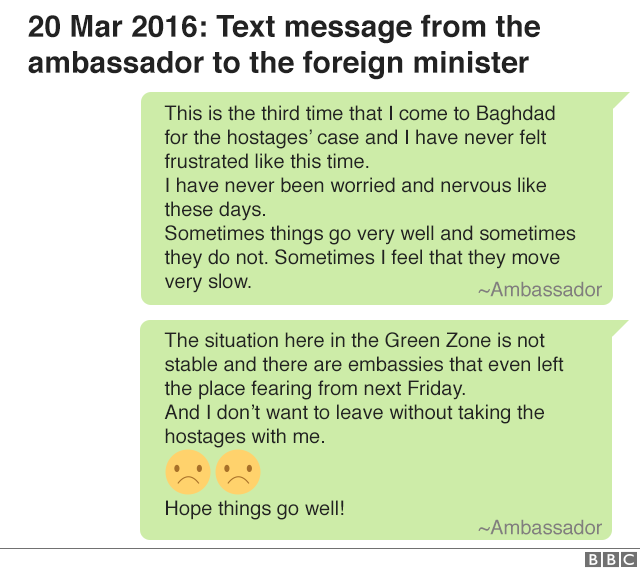

Two days later the ambassador was in the Green Zone in Baghdad, a walled off and heavily guarded part of the city where the Iraqi government and foreign embassies are located.

Iraq in March is already hot. The atmosphere in the Green Zone would have seemed especially stifling: supporters of the Shia cleric Moqtada Sadr were at the gates, protesting about corruption. The staff of some embassies had fled, the ambassador reported. This provided a tense backdrop to the negotiations.

Mr Khayareen waited. But there was no sign of the promised release. He wrote: “This is the third time that I come to Baghdad for the hostages’ case and I have never felt frustrated like this time. I’ve never felt this stressed. I don’t want to leave without the hostages. 🙁 :(”

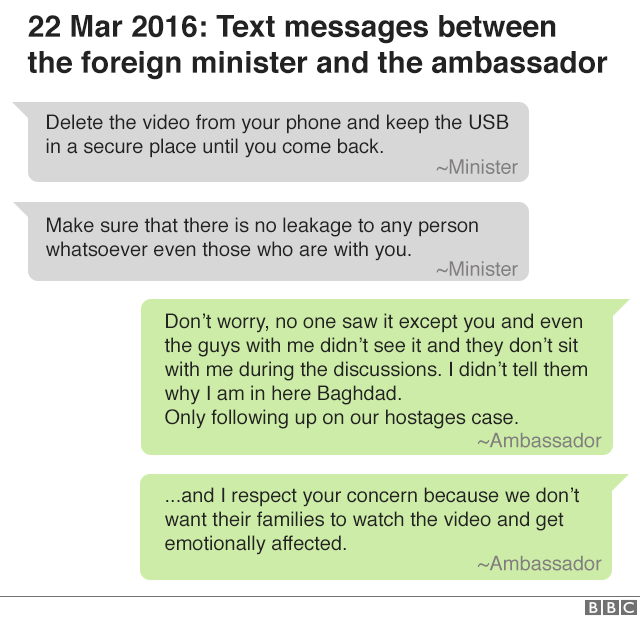

The kidnappers turned up, not with hostages but with a USB memory stick containing a video of a solitary captive.

“What guarantee do we have that the rest are with them?” Sheikh Mohammed asked the ambassador. “Delete the video from your phone… Make sure it doesn’t leak, to anyone.”

Mr Khayareen agreed, saying: “We don’t want their families to watch the video and get emotionally affected.”

The hostages had been split up – the royals were put in a windowless basement; their friends, the other non-royals, and the non-Qataris in the party, were taken elsewhere and given better treatment and food.

A Qatari official told me that the royals were moved around, sometimes every two to three days, but always kept somewhere underground. They had only a single Koran to read between them.

For almost the entire 16 months they spent in captivity, they had no idea what was happening in the outside world.

If money was the answer to this problem, at least the Qataris had it. But the texts and voicemails show that the kidnappers added to their demands, changing them, going backwards and forwards: Qatar should leave the Saudi-led coalition battling Shia rebels in Yemen. Qatar should secure the release of Iranian soldiers held prisoner by rebels in Syria.

Then it was money again. And as well as the main ransom, the militia commanders wanted side payments for themselves.

As one session of talks ended, a Kataib Hezbollah negotiator, Abu Mohammed, apparently took the ambassador aside and asked for $10m (£7.6m) for himself.

“Abu Mohammed asked, ‘What’s in it for me? Frankly I want 10’,” the ambassador said in a voicemail.

“I told him, ‘Ten? I am not giving you 10. Only if you get my guys done 100%…’

“To motivate him, I also told him that I am willing to buy him an apartment in Lebanon.”

The ambassador used two Iraqi mediators, both Sunnis. They visited the Qatari foreign minister, asking in advance for “gifts”: $150,000 in cash and five Rolex watches, “two of the most expensive kind, three of regular quality”. It’s not clear if these gifts were for the mediators themselves or were to grease the kidnappers’ palms as the talks continued.

In April 2016, the phone records were peppered with a new name: Qasem Soleimani, Kataib Hezbollah’s Iranian patron.

Image copyrightAFP/GETTY

Image copyrightAFP/GETTYBy now, the ransom demand appears to have reached the astonishing sum of $1bn. Even so, the kidnappers held out for more. The ambassador texted the foreign minister: “Soleimani met with the kidnappers yesterday and pressured them to take the $1b. They didn’t respond because of their financial condition… Soleimani will go back.”

The ambassador texted again that the Iranian general was “very upset” with the kidnappers. “They want to exhaust us and force us to accept their demands immediately. We need to stay calm and not to rush.” But, he told Sheikh Mohammed, “You need to be ready with $$$$.” The minister replied: “God helps!”

Months passed. Then in November 2016, a new element entered the negotiations. Gen Soleimani wanted Qatar to help implement the so-called “four towns agreement” in Syria.

At the time, two Sunni towns held by the rebels were surrounded by the Syrian government, which is supported by Iran. Meanwhile, two Shia towns loyal to the government were also under siege by Salafist rebels, who were apparently supported by Qatar. (The rebels were said to include members of the former al-Nusra Front.) Under the agreement, the sieges of the four towns would be lifted and their populations evacuated.

According to the ambassador, Gen Soleimani told Kataib Hezbollah that if Shia were saved because of the four towns agreement, it would be “shameful” to demand personal bribes.

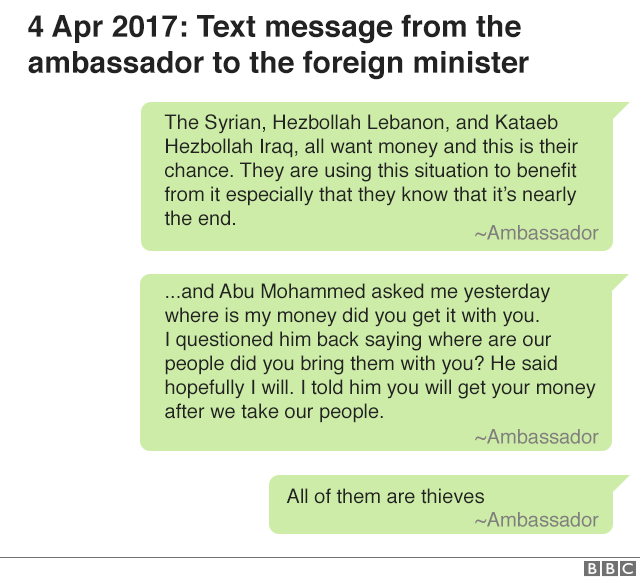

“Hezbollah Lebanon, and Kataib Hezbollah Iraq, all want money and this is their chance,” the ambassador texted the foreign minister. “They are using this situation to benefit… especially that they know that it’s nearly the end… All of them are thieves.”

The last mention in the exchanges of a $1bn ransom is in January 2017, along with another figure – $150m.

The government that gave us this material – which is hostile to Qatar – believes the discussions between Sheikh Mohammed and Mr Khayareen were about $1bn in ransom plus $150m in side payments, or “kickbacks”. But the texts are ambiguous. It could be that the four towns deal was what was required to free the hostages, plus $150m in personal payments to the kidnappers.

Qatari officials accept that the texts and voicemails are genuine, though they believe they have been edited “very selectively” to give a misleading impression.

The transcripts were leaked, to the Washington Post, in April 2018. Our sources waited until officials in Doha issued denials. Then they sought to embarrass Qatar by releasing the original audio recordings.

Qatar is under economic blockade by some of its neighbours – Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and Egypt. This regional dispute has produced an intensive, and expensive, campaign of hacking, leaking and briefings in Washington and London.

The hostage crisis was brought to an end in April 2017. A Qatar Airways plane flew to Baghdad to deliver money and bring the hostages back. This was confirmed by Qatari officials, though Qatar Airways itself declined to comment.

Image copyrightEPA

Image copyrightEPAQatar is in a legal dispute with its neighbours about overflight rights. The question of whether the emirate’s national carrier was used to make payments to “terrorists” will have a bearing on the case – one reason, presumably, why we were leaked this material.

Who would get the cash flown into Baghdad – and how much was there? Our original source – the government opposed to Qatar – maintains that it was more than $1bn, plus $150m in kickbacks, much of it destined for Kataib Hezbollah.

Qatari officials confirm that a large sum in cash was sent – but they say it was for the Iraqi government, not terrorists. The payments were for “economic development” and “security co-operation”. “We wanted to make the Iraqi government fully responsible for the hostages’ safety,” the officials say.

The Qataris thought they had made a deal with the Iraqi interior minister. He was waiting at the airport when the plane landed with its cargo of cash in black duffel bags. Then armed men swept in, wearing military uniforms without insignia.

“We still don’t know who they were,” a Qatari official told me. “The interior minister was pushed out.” This could only be a move by the Iraqi Prime Minister, Haider al-Abadi, they reasoned. The Qatari prime minister frantically called Mr Abadi. He did not pick up.

Image copyrightREUTERS

Image copyrightREUTERSMr Abadi later held a news conference, saying that he had taken control of the cash.

Although the money had been seized, the hostage release went ahead anyway, tied to implementation of the “four towns agreement”.

In the texts, a Qatari intelligence officer, Jassim Bin Fahad Al Thani – presumably a member of the royal family – was present on the ground.

First, “46 buses” took people from the two Sunni towns in Syria. “We took out 5,000 people over two days,” Jassim Bin Fahad texted. “Now we are taking 3,000… We don’t want any bombings.”

A few days later, the Shia towns were evacuated. Sheikh Mohammed sent a text that “3,000 [Shia] are being held in exchange location… when we have seen our people, I will let the buses move.”

The ambassador replied that the other side was worried. “They are panicking. They said that if the sun rises [without the Shia leaving] they will take our people back.”

On 21 April 2017, the Qatari hostages were released. All were “fine”, the ambassador reported, but “they lost almost half of their weight”. The ambassador arranged for the plane taking them home to have “biryani and kabsa, white rice and sauté… Not for me. The guys are missing this food.”

Sixteen months after they were taken, television pictures showed the hostages, gaunt but smiling, on the tarmac at Doha airport.

The sources for the texts and voicemails – officials from a government hostile to Qatar – say the material shows that “Qatar sent money to terrorists”.

Shortly after the money was flown to Baghdad, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and Egypt began their economic blockade of Qatar. They still accuse Qatar of having a “long history” of financing “terrorism”.

Image copyrightREUTERS

Image copyrightREUTERSThe anti-Qatar sources point to one voicemail from Ambassador Khayareen. In it, he describes telling a Kataib Hezbollah leader: “You should trust Qatar, you know what Qatar did, what His Highness the Emir’s father did… He did many things, this and that, and paid 50 million, and provided infrastructure for the south, and he was the first one who visited.”

Our sources maintain that this shows an historic payment, under the old emir, of $50m to Kataib Hezbollah.

Qatari officials say it shows support for Shia in general.

Whether the blockade of Qatar continues will depend on who wins the argument over “terrorist financing”.

Partly, this is a fight over whom to believe about how a kidnapping in the Iraqi desert was ended. Qatari officials say the money they flew to Baghdad remains in a vault in the Iraqi central bank “on deposit”.

Their opponents say that the Iraqi government inserted itself into the hostage deal and distributed the money.

For the time being, the mystery over whether Qatar did make the biggest ransom payment in history remains unsolved.

Update 17 July 2018: Since the article was published, a Qatari official told the BBC the payment of $50m by the Qatari emir’s father was for humanitarian aid. The official said: “Qatar has a history of providing humanitarian aid for people in need regardless of religion or race. Whether they were Sunni or Shia did not factor into the decisions.”