Workers from some of the world’s poorest countries are being paid a pittance to deliver the football dream of the world’s wealthiest per capita state

by David Conn in Qatar. Photographs by Tom Jenkins

“The agent said to me: ‘Qatar is the richest country in the world; you can Google it,’” one man told me. “He said we would earn a ‘huge salary’. But when we came here, we found it was the opposite.”

Al-Rayyan is one of seven dazzling stadiums being built around the Qatari capital, Doha, in addition to the reconfiguring of the sole pre-existing World Cup venue, Khalifa International, which was completed last year. The total cost is between $8bn and $10bn, according to the supreme committee’s general secretary, Hassan al-Thawadi. Representatives of the supreme committee and their contractors walked us on a tour of al-Rayyan, being built to Fifa’s highest specifications. In heat and glare, 10 men from India, Nepal and Bangladesh, the most common countries of origin for Qatar’s migrant workers, were neatly cementing square vents beneath every seat, in time for a tournament due to begin in exactly four years’ time – on 21 November 2022.

The supreme committee has pledged high standards for workers’ rights and welfare after torrential criticism of conditions by human rights organisations and the media, and they showed us some of their workings. The health and safety manager, Abdulla Ahmad al-Bishri – who studied engineering at South Tyneside college in north‑east England – showed us records of exemplary safety standards. Bishri and representatives of AECOM, the American project manager, showed us an accident frequency rate of 0.005% and told us 7,000 people had been trained for working at height and about the measures they use for mandatory breaks when the heat becomes impossible; the canteens of water containing electrolytes carried by all the workers; the safety signs in English, Hindi and Tamil; the confidential grievance hotline.

- Top: Migrant workers walk up into the stands at the construction site for the al-Rayyan stadium. Below: A labourer drinks water at the site.

At the camp, accommodating 4,500 men, they guided us around the improved facilities adopted widely to replace dire, overcrowded, unsanitary dumps that still plague the country. Official government standards still allow four workers to be accommodated in one room but bunk beds are outlawed. Food is cooked and supplied to good nutritional standards; there is a medical centre on site, plus a gym, a football pitch and a computer room with free internet to help the men, all away from their families, communicate with home. There is also a free laundry service – “Just like a hotel,” one of our guides said.

So when I finally sat down to talk to the workers, I was almost ready for them to say they could hardly be happier. Aged between 28 and 38, all married with at least one child, they acknowledged that the camp was decent; they had Ghanaian friends in other camps which were dirty, and had no food or amenities. Then they started to talk about the pay.

“It is hard to be away for so long,” one said. “Sometimes the family want to have you in their midst – and you may not have money to send them. We were supposed to earn something big – but we earn small.”

Asked how much, one of them opened his eyes wide in exasperation, and said: “650 a month basic salary.”

For building one of the prestige stadiums designed so Qatar can dazzle the world in 2022, eight hours a day, six days a week, this is £140: a little under £35 per week; £5 per day.

Like all the migrants working in Qatar, the money they send home is not extra; it is primary income to support their families. The Ghanaians said they still have expenses in Qatar, although food and accommodation is taken care of, and the money is not enough.

- Top: Accommodation blocks at the QDVC migrant workers labour camp near al-Khor. Below left: A bedroom shared by four men and, right, signs in the main office at the camp.

One man, 38, who said he had two sons, aged 10 and two, explained: “Our system in Ghana is the extended family. When anybody needs help, they come to you. They know we have travelled to Qatar and ask us for money, but we don’t have it. I do not have enough to feed my family. The money is not what we expected to get. We think about this all the time.”

They said they did not believe that raising a grievance would change anything. A 29-year-old man said: “We don’t have help from anywhere, we have to support and encourage ourselves every day. Otherwise what will you do: kill yourself?”

The supreme committee always argued that the scrutiny arising from the success, in 2010, of the bid for 2022 could be a catalyst for reform. This tournament is, inescapably, a World Cup of inequality, hosted by the per capita wealthiest country, built by men from the poorest.

In October 2017, the government headed off an impending formal commission of inquiry into the conditions of its migrant workers by the UN agency the International Labour Organisation, by agreeing to work with the ILO on a programme of reforms. In a statement from Thamer al-Thani, Qatar’s media attache in the UK, the government said it was “committed to working with our international partners, including the ILO, to improve the rights and living conditions of our guest workers. Qatar welcomes all constructive feedback of our labour system and we have never shied away from the idea that further reform is required.”

A major breakthrough was hailed in September with the abolition for most workers – although not domestic staff – of the loathed exit permit, which prevented people at the end of contracts returning home without their employers’ permission.

Houtan Homayounpour, head of the ILO’s Qatar project office, describes that as a beneficial change, and he lists other results: settlement committees for workers’ disputes, legal protections for domestic workers, and a commitment to ending the notorious “kafala” system, which ties workers to a single, sponsoring employer.

The supreme committee has itself implemented a system for reimbursing workers some of the recruitment fees they paid to agents. Mahmoud Qutub, executive director of workers’ welfare, told us they expect to pay 89m rials, £19m, to 39,000 workers over the next three years, an average of £487 each.

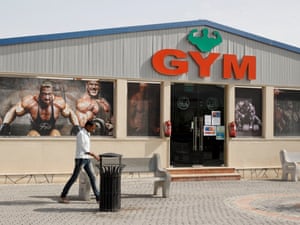

- Clockwise from top left: The gym at the Challenger trading and contracting labour camp near the al-Rayyan stadium; migrant workers have a game of football at the camp; labourers play table football and returning to the camp from a shift.

“Actions speak louder than words; real changes have been made,” Homayounpour said. “Is it perfect? No. The government admits that and there is much more to do. There is genuine progress but challenges remain, which we are working on.”

The government has committed itself to introducing a minimum wage, and while research continues into a recommended level, a temporary figure has been agreed. But it is only 750 rials a month – £160, a little under £40 a week.

The supreme committee said its contractors at al-Rayyan were instructed in September to pay the advisory minimum wage of 750 per month to all employees. They said they investigated the pay of the Ghanaian men and did find one of them being paid 650. “This has now been rectified,” a spokesman said.

The senior figures we talked to seemed to struggle to see injustice in the painfully low pay, saying it was much more than people would earn in their home countries. The “remittance” of money by people working in wealthier countries to low- and middle-income countries is indeed a global phenomenon; in 2017, the World Bank has reported, $466bn was remitted, with India the biggest recipient, of $69bn.

One expert in Doha said that when trying to understand the resilience of so many migrant workers in tough conditions, it is important to remember the hardships from which they have escaped. “In their home countries, many of these people live in incredibly poor, subsistence conditions,” he said. “There are no jobs, no infrastructure, no roads or drinkable water in some areas, and labour exploitation. We are seeking to address important issues, but they see their ability to work in Qatar and send money home as a huge advance.”

- A warning sign at the al-Rayyan stadium site.

The government is keen to showcase the strides it has made to improve welfare, and it organised access to two camps that meet its standards. The first, up a desolate road at al-Khor to the north of Doha, past a sandy stretch pockmarked with twisted remains of metal sheds, accommodates 3,000 men working for the French-Qatari construction joint venture, QDVC. The company’s staff and government inspectors proudly showed us the bare rooms shared by four men, separate clean toilets and showers, large gym and internet room – and while we could appreciate the physical basics being provided, we found the place painfully bleak.

The government’s policy to address the large problems with inadequate accommodation, often run by smaller companies, they said, has been to commission “Labour City”, a vast, purpose-built complex behind high walls and railings, opened in 2015 to accommodate 100,000. In total five camps are planned, to move up to 600,000 to the solid buildings and better facilities, which incorporate clean toilets and showers, catered food, communal green spaces, a large mosque and places of worship for other religions, medical and recreational facilities. Famously next door is Asian Town with its mall and restaurants for workers, and a 15,000-seat cricket stadium and an amphitheatre for outdoor events.

In a corporate presentation my guides put on before the tour, Labour City was said to be born of “the wise vision of the state of Qatar”. The language was telling, though: the presentation said the camp was built to provide a “proper environment” for “this category of society”.

In the internet room upstairs in one of the blocks, a lone man was watching YouTube clips from home, earphones on. He was 38, he said, from a village in Uttar Pradesh, India. He had been in Qatar for seven years. He was married with three children, aged 12, eight and five. “Before, I stayed in different camps, in wooden cabins. Now it is better, safer, to be in a concrete building. And it is good to be near the shops and supermarket, because some camps were far from town.”

Asked how it felt to be so far from his family, he said: “I miss them. When I feel too much pain, I call them. But I am earning enough money to support my family and relatives. So I am feeling relaxed.”

To meet workers outside the designated camps, a man with local knowledge took me to a street corner in the Msheireb area of downtown Doha. Round the corner from the Corniche strip of beach, and the Souq Waqif complex of shops and restaurants, the area turns suddenly into a rundown street transplanted from Bangladesh. My interpreter walked into the crowd and asked two young men how life was for them. He explained loudly that I was from a newspaper, that newspapers had reported the oppression of the exit permit, the government had read the coverage, and the exit permit had been abolished, so they should talk to me in the hope their lives might change.

Within minutes, a huge crowd of men had gathered, all telling stories of despair. Their experiences made life in the camps seem secure, enviable by comparison.

“People here are not working,” one man said. “Or they are working but not being paid. There is no work, or very low pay.”

- Migrant workers look across the water to the skyscrapers of West Bay in Doha on their day off.

They had all paid agents for visas, one or two had purported sponsors that proved to be a mirage; one man unfolded a scrap of paper with his sponsor’s name on it, a company he had never been able to find.

“The agents said Qatar is a very rich country, with the 2022 World Cup; there you can earn good money,” one Bangladeshi man, 28, told me. “But here when you work, the company does not pay you.”

They had found bits of work on construction projects, they said, as electricians, plumbers, firefighters, from subcontractors, supply companies, who did not pay them or folded. One man just stood and shook his head, repeating “supply companies” over and over again. He was 38, he said, with a wife and 10-year-old daughter in Bangladesh, and was in agony because he could not send money home and did not have the fees to keep his daughter in school. His wife criticised him for going to Qatar, because rickshaw drivers in his village were making money to support their families.

Another young man, 26, shouted that he did not have money even to eat: “No rice, no vegetables, no chicken,” he said. “Only chapati.”

His eyes had a look of pleading. I asked how long he had gone without proper food.

“Eight months,” he replied.

We promised I would report these stories, and that the government and the supreme committee organising the 2022 World Cup would read the coverage. Within five minutes my interpreter and I were driving along the Corniche, past the formidable, floodlit Emiri Diwan, Qatar’s parliament building. Soon we were up in the West Bay, among the towers, hotels and restaurants where fans will enjoy exquisite service in 2022, amid the signs of the supreme committee, with their promise for the World Cup to “Deliver Amazing”.