Original story by Euronews b

A Kuwaiti artist has created a cemetery of books to protest the government’s ban on thousands of pieces of literature in recent years.

The art installation itself, named “A Cemetery of Banned Books”, consisted of more than 200 headstones and was erected close to the location for Kuwait’s annual book fair. It was removed by authorities several hours later.

Speaking to Euronews, artist Momhammed Sharaf said he had two goals when designing the cemetery.

“The first was to shed light on the banned books,” he said. “The second is to show people that we can say ‘no’ in a very peaceful way, without manifestations, and without writing in journals.”

“The secret behind the success of the attempt is that it did not disrupt the people’s movement, and it did not ruin anything. It speaks for itself.”

Sharaf was inspired to create the artwork by the news that more than 4,000 books had been banned by Kuwait in the last five years, according to the Ministry of Information.

Included in this ban are classics such as Victor Hugo’s “The Hunchback of Notre Dame”, and Egyptian Nobel Prize-winning author Naguib Mahfouz’s “Children of Gebelawi”.

Social media uprising

Sharaf’s art protest is nothing new.

On social media, an online discussion has ensued with Kuwaiti writers and literature fans debating the effect and relevance of the continued bans on literature.

The Arabic hashtags “banned in Kuwait” and “don’t decide for me” have been trending on Kuwaiti social media networks as citizens across the Gulf nation protest the ongoing bans.

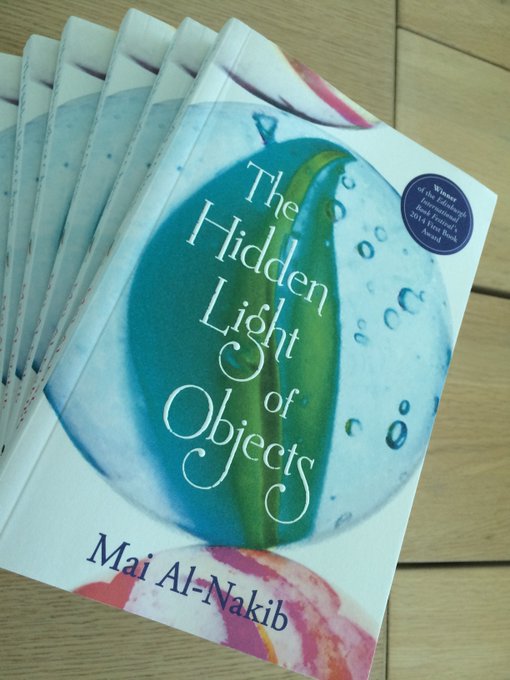

Kuwaiti author Mai al-Nakib tweeted in September that she returned to her home country to find her book, “The Hidden Light of Objects”, had been banned.

“What I felt upon learning from a tweet that my book was now officially banned in the country of my birth was an overriding sense of exhaustion,” she wrote in a later blog.

Another Kuwaiti author, Mohamed Gazi, wrote about his reaction to finding out his book had been banned for “excessive use of the f-word.”

“I was left with the only choice, of course, to edit what they wanted me to edit. And I’d rather get my book banned in one country than change the contents that I worked almost a year to create.”

However, not everyone is protesting the censorship.

Writer Hayat al-Yaqout, also from Kuwait, tweeted in support of the government, pointing out that if governments won’t censor material, parents are then forced to become the censors for their children.